Representation and Allegory

“…I am less interested in what these books say than in how they say it. This approach reveals that studies that seem quite different – historical versus ethnographic, academic versus popular – are nevertheless bound by certain common assumptions…” (Rubenstein, 23)

So begins Steven Rubenstein’s exploration of the Shuar healer Alejandro Tsakimp. For it is not only what is being depicted, but how that depiction is taking place, which establishes our understanding – how we learn what we are learning, or how we know what we know. This is an elaborate process, weaving between the representation being made and the assumptions which come to bear upon the subject, not only those of the author, but those of the audience and even those of the subjects themselves.

How is information being presented? What bearing does the position of the author have upon a representation, and to what degree does the utilization and incorporation of “fact” and “fiction” affect the creation and consumption of information? Is there such a thing as truly accurate representation? Is there one method which serves representation better than another?

To this end, I will explore four examples, a kind of “historical versus ethnographic, academic versus popular” approach of my own, discussing the various ways in which the representations being made in each of these accounts is presented, and how these methods affect our (the audience’s) understanding of that information.

Part One: Referential Fiction as Essential Representation

At Play in the Fields of the Lord by Peter Matthiessen

In At Play in the Fields of the Lord (Random House, 1965), Peter Matthiessen presents his readers with an account of disparate peoples in the South American rain forest – Protestant missionaries, “stateless mercenaries”, the local government and “elusive” Niaruna Indians – whose lives are drawn together in complex and interactive ways. More than anything the story becomes an examination in morality. The attempts at spiritual intervention by the North American missionaries, the Huben and the Quarrier families, in the lives of the Niaruna Indians costs the Quarrier’s their son, Billy, who dies of blackwater fever at a remote mission outpost – and will come to claim the sanity of Hazel Quarrier and the life of Martin Quarrier. Matthiessen makes it clear that these missionaries, as well as their Catholic counterpart (led by another Western outsider, Padre Xantes – though he is not as far removed from the history of the country as the U.S. missionaries are and will, as the story unfolds, suffer less for it) never truly convert the natives – at best the Indians play at being one religion or another, working both Catholic and Protestant sides for quality and quantity of goods given in exchange for their souls. Thus Matthiessen illustrates how truly superfluous the attempt at religious conversion from outside sources truly is. Furthermore, not only are these attempts at conversion deadly for those performing the operations, they are destructive to the people ostensibly needing the spiritual assistance in the first place. When the character Lewis Moon, a Native North American Indian mercenary, deliberately crashes his plane in the rain forest to live with the Native South American Niaruna Indians, he brings with him a biological link between the Western, outside world and this Indigenous inner sanctum – allowing the spread of disease and rapid destruction of the Niaruna people, Moon in many ways mimetically replicating the role the U.S. Government played in spreading smallpox to his ancestors in the north.

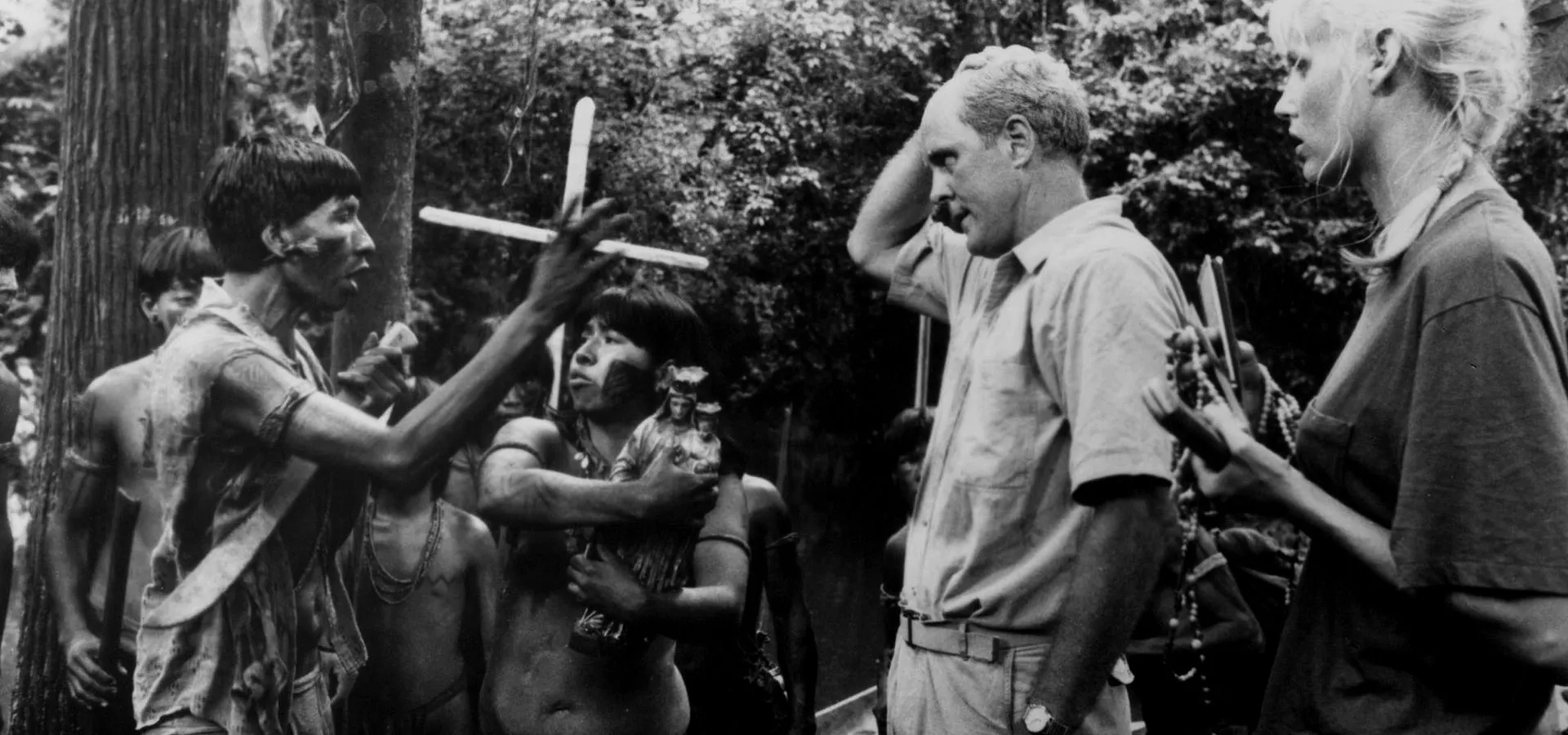

Still from the film version of "At Play in the Fields of the Lord"

How interesting, in the sense of a Cliffordian “redemptive Western allegory,” that the North Americans destroy not only themselves and those they seek to aid, but do so both deliberately and accidentally. And how moralistic (in a Western context – in which this story was created and through which it is, in our discussion, being read) in this story of Western intervention and forced redemption, that the closing of the novel would focus on the Native American Lewis Moon, reborn on the river shore, the only person in this depiction who leaves the story better off than when he entered it.

The question now becomes, Should this story be given the credence necessary to engage it on a moralizing level? Is there anything presented to us in Matthiessen’s story which disassociates this representation from standard Hollywood entertainment fare, thus increasing its supposed authority? Is my interpretation of At Play… as presented above accurate, or even allowable? These questions require an examination of the elements which comprise the representation being made by Matthiessen.

The first issue is that of “fiction,” or a created account. At Play… is not presented to us as an ethnographic, truly accurate account (the back cover of the book states clearly, “FICTION / LITERATURE”). Yet the information, even though it is presented in a literary manner, directly utilizes the real – the place names, the Indian tribes, and anthropological-historical parallels – which leads the reader to believe that while the work is one of fiction, it may very well be based in reality. This is important because of the authority such a manner of historically-based (or biased) depiction carries with it. For example, there is a character in At Play…, a Westernized Indian who goes by the name Yoyo, who acts as an intermediary between the indigenous Indians of the rain forest and the Westerners (Catholics, Protestants, and mercenaries alike). Yoyo helps by providing information to these groups, and in return is rewarded with Western goods (“…his white-man’s haircut…and the red shirt which, exposing his crucifix, was so large for him that it covered the mission shorts…” [Matthiessen, 314]). How similar is this character to one which Michael Taussig, in Mimesis and Alterity, shares with us? Ruben Perez, the Westernized Cuna Indian, who was enlisted to work with Baron Erland Nordenskiold, sharing information about the Cuna for Western consumption. The photograph of Ruben Perez sitting in a Western dress suit, hair neatly parted, provides an interesting parallel between two men, one real, one (supposedly) fictional. Did Matthiessen aim to mimetically recreate his Yoyo in Perez’s image in an attempt at accuracy?

Whatever the answer (I don’t know how much Taussig Matthiessen has read, if any), the point I wish to illustrate with this example is the way in which Matthiessen’s work of fiction calls on other, established segments of anthropological study, and that there exists a legitimizing relationship between “reality” and “fiction”, a legitimating which goes both ways at once.

Matthiessen’s work has its roots in the real – yet he is at the same time constructing a notion of the real, in which the representation he offers is situated within the same frame as ethnographic representation. The frames of each, the realistic account and the fictional account, direct us in the same way – they are, for all purported inherent differences, both being presented to us as real. Hence, parallels between the two seemingly disparate realms such as Niaruna Indian spirit-animal myths (the jaguar, the fer-de-lance) and Cuna Indian spirit-animal myths (the jaguar, the peccaries) or Niaruna Indian sympathetic magic (Boronai’s medicine for Billy Quarrier and his masato-induced death-trance) and Cuna Indian sympathetic magic (nuchus figurines used in healing magic) at once serve to legitimate each other.

Furthermore, Matthiessen allowed aesthetic concerns to override the referential descriptors in his account – truly merging the two seemingly distinct realms of reality and fiction. This is only natural, not only because Matthiessen is interested in creating a work of fiction, but also because the combination of “aesthetic constraints” and “referential constraints…halts what we might call the vertigo of notation,” without which “any view would be inexhaustible by discourse.” (Barthes, 144) This combination of fact and fiction establishes frames by which the story can be contained, and at once blurs any concrete distinctions between that fact and fiction. But more importantly than this, the merging of realistic referents and the aesthetic constraints which fictions utilize give Matthiessen’s account a depth which standard description lacks. It is here, in this coupling, that Barthes recognizes the strength of fiction to exhibit the power (and “truth”) of “analogical” representation while at the same time creating new referents from the shells of others.

But examining the fact/fiction paradigm alone does not answer my introductory questions. That a fiction is being created and used belies the fact that there is a person making and using this fiction – the author. Once we recognize and accept the existence of a person making the representation, we cast our glance further along to see that there is also someone consuming the representation being made – the viewer, the audience, ourselves.

Concerning this binary, the author/audience model, Stanley Fish explains the ways in which context is informed by the interpretive perspective of the viewer (or reader, or listener, etc.), a perspective which is intricately entwined into the context by which the work is being consumed. Fish claims that there is no possibility of a de-cultured, de-institutionalized, de-specified interpretation – there is no way to escape the context in which the reading of a work has been made. “There are no moves that are not moves in the game.” (Fish, 355) The content and the form of that content, as well as the context in which that content is being consumed, are inextricably linked (It is in this light that I can justify my reading of Matthiessen’s account of At Play… as being a story of morality, in which the history of U.S. relations to indigenous peoples – Native American Indians in particular – is very much a part of my understanding of the interpersonal/inter-religious/inter-political relations addressed in the story. Were I instead reading At Play… in 1819, in the newly “purchased” state of Florida, my take on Native American Indian relations – to the Seminole tribe specifically – would perhaps be different). And it stands to reason that if the context in which a work is viewed is important to its interpretation, then so is the context in which a work is created: enter the author and the context of creation, the double-edged sword by which works (fictions, ethnographies, visual art, etc.) are viewed and consumed.

James Clifford furthers this argument when he states that a representation cannot be separated from that being represented and that engaged in the making of said representation. Clifford also states that all accounts, due to this link between the represented and those making the representation, as well as Fish’s link between the contexts of creation, existence and consumption, lead to the creation of allegory. Every account is, on one or more levels, an allegorical account. This is unavoidable – we are susceptible, malleable creatures, and our accounts will always be tinged with that fact. Thus, every story told will contain its own allegory – no matter how hard the author strives to keep that allegory out.

We could argue that Matthiessen’s account of the Niaruna Indians, or the North American Protestant missionaries, is allegorical on a number of levels (I have offered one, the allegory of Western intervention in Indigenous affairs). And were we to take Fish to heart, an interpretation generated within our own cultural context could very well be acceptable (as is the redemptive interpretation of Lewis Moon I offered earlier). But for our purposes, understanding that all accounts, Matthiessen’s included, hold the potential for allegory is the vital element. Vital because of the question Clifford poses, the question which takes the author and his or her aims toward representation to heart: “How, precisely, is a garrulous, overdetermined cross-cultural encounter shot through with power relations and personal cross-purposes circumscribed as an adequate version of a more or less discrete ‘other world’ composed by an individual author?” (Clifford, 25) Or, how can the author of a work truly remove him- or herself from the context and assumptions from which he or she is placed? How can anyone be de-cultured, de-institutionalized, or de-specified enough to make a truly accurate representation? It would seem that the only way around this conundrum would be to recognize the inherent dilemma in this situation and move beyond it.

The author is always present (in many and diverse ways) in the representation, no matter how he or she may try to absent themselves, regardless of whether or not the work is presented as an historical ethnography or a work of literary fiction. The power relations which entwine themselves with every representation and with every author can be covered over, but they will continue to exist. Does an alternative exist?

Here we arrive at the possibility that Matthiessen, in creating a fictional account based upon non-fictional information, or with (at the least) non-fictional referents, to have utilized the most essential form of representation. Is not Matthiessen’s open avowal of the fiction he is creating, culled from ethnographic sources, presenting valuable information about a people (here, those in a South American rain forest, ourselves, and the relationships between the two) while admitting that the work he creates is rife with allegorical underpinnings and shot through with power relationships? Is this approach not akin to saying, “Yes, I am engaged in the creation of fiction, of allegory, and I am one-and-the-same with the representation I am providing. I cannot be removed from the account I have brought forward. Know this, recognize it, and move beyond it to see that my account, though rife with human authorship, is also full of information which may be of use. This representation is just as real as the next, and holds as many possibilities.”

Part Two: Allegory on Allegory, Mimetic Excess

Mehinaku: The Drama of Daily Life in a Brazilian Indian Village by Thomas Gregor

Thomas Gregor, in his ethnographic account Mehinaku: The Drama of Daily Life in a Brazilian Indian Village, sets out to explain the way of life of South American Mehinaku “…by viewing them as performers of social roles.” (Gregor, 1)

The Mehinako village of Uyapiyuku. Photo by Thomas Gregor.

To this end, Gregor utilizes what he terms a dramaturgical metaphor, creating an allegory of the theater (drama) through which we (Westerners) can more fully comprehend the complex system of Mehinaku society. It is an effect which aims to address Hayden White’s question of the nature of narrative: how to “translate knowing into telling”, how to “fashion human experience into a form assimilable to structures of meaning that are generally human rather than culture-specific.” (White, 1) How can the information presented make sense to the consumer of said information? How can we “translate difference into similarity” (15), but still present the information in de-cultured, de-institutionalized, or de-specified terms?

Certainly this is a tricky task, for Gregor spends time establishing the validity of such an enterprise (in fairness, it should be noted that Gregor does comment as to the “dangers” of this method, and devotes one paragraph in the early pages to the problems found therein [Gregor, 1,8]). Yet, as soon as Gregor calls forth on the historical validity of Shakespeare himself (“The role concept in social science…was given memorable form by Shakespeare.” [6]), he begins to justify his approach based upon early- to mid-20th century sociological definitions of the “role”, from which parallels between society and theater developed. In fact, Gregor (with the aid of Erving Goffman) dictates many examples of Western cultural conventions in which the dramaturgical metaphor is enacted: The doctor in his office (7-8), the furniture salesman, the pool-hall hustler, and even Sammy Davis. (10)

Without disparaging frames (by which all our social interactions are dictated, the doctor in his office and Sammy Davis included), initially I find something problematic in Gregor’s approach, something more Cliffordian in scope, where the idea of allegory is taken, by Gregor, to an extreme level through his use of the term “dramaturgical metaphor,” which becomes grounded in the Western notion (ageless though it is) of drama – not simply an enacting of roles as perceived or handing down through the generations, but a drama, a metaphorical performance by some for the consumption of others. If we take Gregor’s “metaphor” as metaphor, we see that he is predicating the social roles of a group of people in specifically Western terms – the Mehinaku are doing what they do for our utilization (as ostensibly “scientific” as their performance may well be).

Gregor describes Mehinaku society as “a kind of social drama,” calling the people actors who “communicate and move in and out of play” in “a great theater in the round [the Mehinaku village proper]” (247). In one section, Gregor illustrates how one of the tribe members, a young man named Kehe, undergoes an “informal sanction” by which, to atone for shameful conduct, he hides in an abandoned house. The members of the village soon come to believe that Kehe is in what Gregor terms (though this is something he credits the Mehinaku for) “puberty seclusion,” whereupon the village labels Kehe’s wife his “mother” and believes that her new “role” will be one of caring for Kehe, bringing him “water for bathing as would any parent who had a child in seclusion” (239). Clearly, parts are being played by the members of this tribe, roles which are played out and changed, such as “husband” to “child” or “wife” to “mother” and even extras to directors (as the members of the tribe in this one scene become).

What happens when the inherent allegory of the ethnographic text is so clearly addressed? What happens when the problematic nature of authorship is not only spoken to, but utilized? Let us not forget that Gregor is the one who has introduced the term “dramaturgical metaphor,” regardless whether or not the Mehinaku truly are performers in the great drama of life. Here I find myself wanting to credit Gregor with something that Matthiessen missed. I find myself wanting to say that, while addressing the problems of representation in a straightforward manner seems to neutralize them (as my mimetic Matthiessen did when he stated in the first section that “…I cannot be removed from the account I have brought forward. Know this, recognize it, and move beyond it…” – and as Gregor seems to do by integrating the allegory in his work to the extent that he does), something tugs at my shirtsleeve, and I find myself asking another question: Is the allegory of the theater, the allegory which is found in Gregor’s Mehinaku, the same allegory which Gregor uses to his advantage, the only allegory found in this ethnography? Or is there another allegory at work here? An allegory in the Cliffordian sense, hiding just below the surface?

Is this Taussig’s “mimetic excess?” Think about the dramaturgical metaphor, specifically as it plays in Gregor’s account, while reading this paragraph from Taussig:

Mimetic excess as a form of human capacity potentiated by post-coloniality provides a welcome opportunity to live subjectively as neither subject nor object of history but as both, at one and the same time. Mimetic excess provides access to understanding the unbearable truths of make-believe as foundation of an all-too-seriously serious reality, manipulated by also manipulatable. (Taussig, 255)

I would argue that Gregor’s account, though rife with the potentiality to exist as mimetic excess, is rather different. It is a mimetic excess which is being imposed – the Mehinaku, though they speak of themselves in terms rather conducive to the dramaturgical metaphor (though through Gregor’s voice), are still being engaged in that metaphor by Gregor through his account – the Mehinaku are not flipping back and forth between their reality and a theater as performed for observers (though they do it for themselves). Gregor is flipping us between those multiple realms; the freedom enacted by mimetic excess is lost to us all.

Take this example, from the concluding chapter of Gregor’s book:

As soon as we [Gregor and a three-man film crew] arrived and I had explained the purpose of the film, the Mehinaku enthusiastically began to participate as actors, directors, authors and stagehands…ShumoI, on his own initiative, organized the children in a series of “spontaneous” games of role playing that he thought would be interesting to the kajaiba… (353)

Here we find a very literal example of the Mehinaku performing for Gregor, though he tells us that they are doing this of their own volition. Is this truly the case, or is Gregor supplying us with an example of just how true the dramaturgical metaphor is in the lives of the Mehinaku?

Of course, this is all predicated on the allegorical underpinning of Gregor’s metaphor. What would happen if we were to approach Gregor in a more literal manner, something closer to Taussig, thinking of “dramaturgical metaphor” as “mimesis.”

If we take Kafka’s very own Red Peter as an example, we see that mimetic reproduction has incredible instructional ability – play has an intrinsic educational value. It is in this way that the Mehinaku, in order to survive, constantly play at being Mehinaku. If, according to Kafka, Taussig and Gregor all knowledge is experiential, that people learn from watching and mimetically reproducing the acts and behaviors of others, then we see how necessary an event this is for survival, the Mehinaku included.

Is this the “dramaturgical metaphor” stripped of its literal metaphor? The Mehinaku “play” and we address them as “actors” on “stage” because as they perform their roles, they fill and complete those roles. If this is the case, we can approach the earlier example of the Mehinaku performing for Gregor and his film crew as something more complex: Here, the Mehinaku, in performing as “actors, directors, authors and stagehands” are responding to a new situation which the tribe is facing, that of a Western anthropologist entering their community with a “three-man film crew and bulky sixteen-millimeter equipment,” something they (according to Gregor) never encountered before. In this regard, the Mehinaku are playing at being (and thus learning how to be) what they think the outsiders want them to be – a methodology which might aide them in their relations with this new “tribe.”

So what happens to the actor/audience binary (which posed so many problems earlier) when we offer this scenario: are those involved in the “play” contingent upon an audience for their existence? Will the Mehinaku continue to “play” once the last audience member has left, or once Gregor has fallen asleep? Or are there still other observers present? Can’t the Mehinaku be at once actor and observer? Now the audience is no longer strictly Western and the Mehinaku are no longer performing in purely Western terms, for purely Western ends. The earlier concern of a culturally-dependant methodology is neutralized, and it becomes clear that Gregor speaks in terms of the Mehinaku performing not only because this allegory makes our understanding of their culture more relatable to our own experience, but because the Mehinaku truly are playing at being Mehinaku.

Just as Matthiessen’s representation utilizes a realistic referent on which he strengthens his fiction, Gregor utilizes a referent – here, the theater – for the very structure of his account. Could Gregor, perhaps writing after Taussig, have spoken in terms of mimesis and a mimetic theory of performance with equal success? Though Gregor’s term “dramaturgical metaphor” is fraught with difficulties – depending upon your interpretation of “metaphor” – it does deserve credit as the foundation from which mimesis will eventually be drawn. As a representation, Gregor’s account still finds itself mired in the problematic nature of authorship and interpretation (and its inherent power relationships). But the strength of speaking in terms which “translate difference into similarity” afford Gregor, with a Matthiessen-esque admittance of that authorship and interpretation, an informative opportunity to gaze into the lives of a distinct people, from which we can cull our own interpretations.

Part Three: Western Man and Noble Savage (Like Father Like Son)

The Emerald Forest by John Boorman

“This film was made in the Rain Forests of the Amazon and is based on real events and actual characters.”

So we learn at the beginning of John Boorman’s film, The Emerald Forest (Embassy Films, 1985). There is an incredible amount of power behind those twenty words. In an instant (and more importantly, from the film’s outset), we are told that what we are watching – though a Hollywood movie, replete with Hollywood action, adventure, and drama – is real, an accurate re-telling of specific events and specific people. The voice in the beginning is, foremost, a written voice – it is completely devoid of humanity, it is non-emotive, it is official. Furthermore, it enlists the legal/political form of discourse (Barthes, 144), it is an “objective voice” (131) which does not allow room for a questioning of its source, which does not allow for an examination of fallibility, because it is not human, it has no emotion, it cannot be incorrect. There is another authority present in Boorman’s representation, and that is the authority of the camera, the frame through which Boorman directs our attention. The camera is also “objective” (though certainly the person directing the camera is not – a fact not often drawn attention to and in this case a fact we are purposely directed away from by use of the introductory statement), and we are once again led down the path of matter-of-fact accuracy. Thus, when we watch the events of the film unfold such as Tommy’s abduction or the final breaking of the dam, we are seeing reality – The Emerald Forest is actively engaged with the construction of the real, though a referent hindered by a flawed representation.

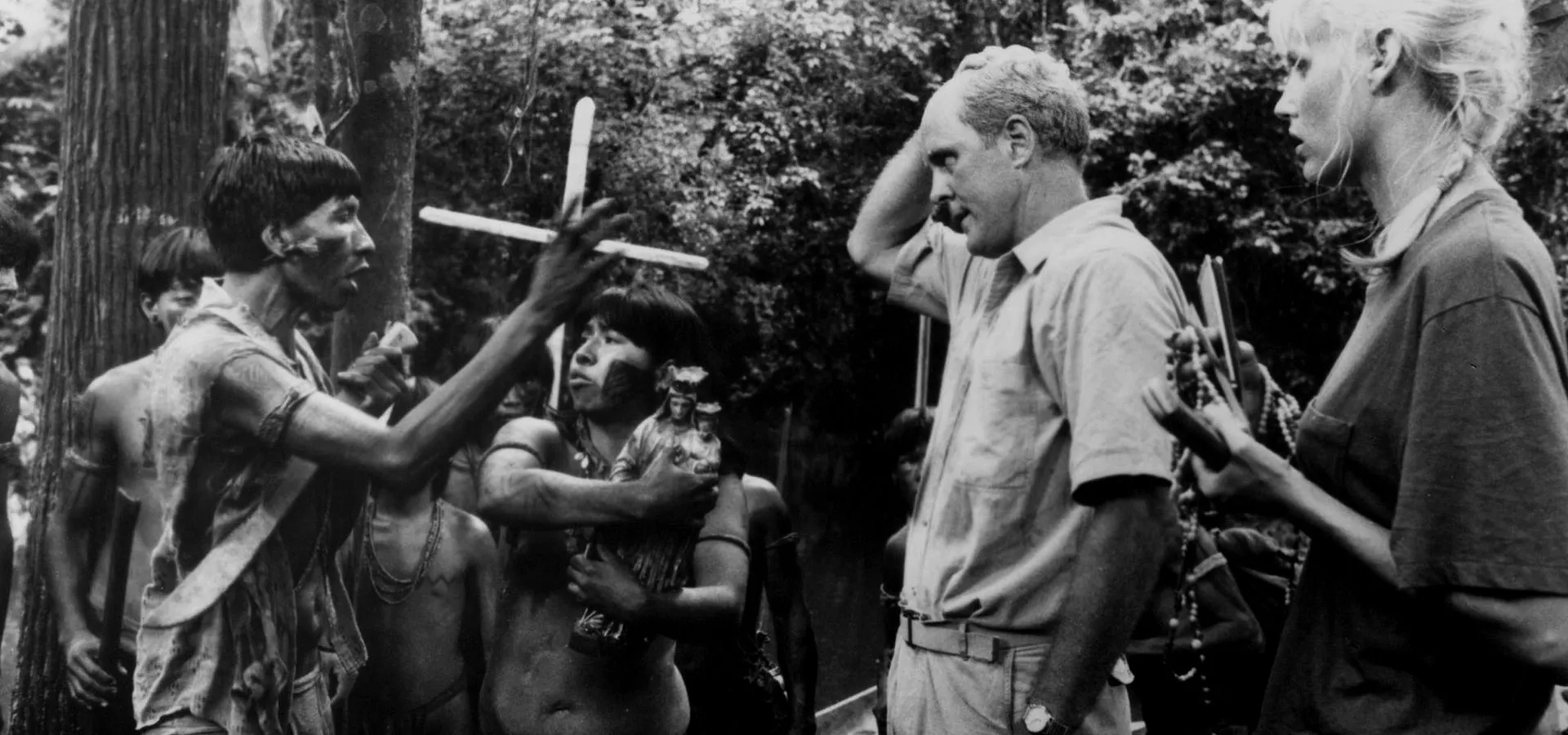

Still from the film "The Emerald Forest"

Why so much attention to the authority of the film? Because joining the issue of authority with the matter of cultural stereotypes, we see that when viewed in conjunction Boorman’s representation is not only inaccurate, it is downright harmful – it presents stereotypes and leads us to believe them to be correct, accurate representations of the people involved. Granted, cultural stereotypes were not invented with Boorman’s film (Matthiessen too pulled from cultural assumptions, while at the same time created others in a cycle of perpetuation), but the authority of the film’s frame as well as the statement beginning the film and the reality being constructed by the film all aid in the production and perpetuation of stereotypes.

Knowing that Hollywood norms dictate the use of drug-running, prostitution, and lots of gun-fire in their movies (especially those of the 1980s), let us pair down to two of the larger stereotypical representations that Boorman provides: the noble savage and the dark savage (we could also include a third contender, that of the Westerner).

In what were perhaps the two most difficult representations to endure, Boorman provides us with the “Invisible People” and the “Fierce People,” two opposing tribes living in the Amazon. And while it is the Invisible People who kidnap the young Tommy Markham and raise him as their own (much – we must keep in mind, and are constantly reminded – to the never-ending dismay of Tommy’s natural parents), we are still lead to believe that the Invisible People are not cruel-intending child snatchers but rather kind, naïve, water-frolicking people of the forest, constantly hiding from those who would hunt them, kill them, and take their women. A prime example of this simple intention is the Invisible People’s chief’s reason for taking Tommy in the first place – he could not let such a kind child be raised in the land of the “Termite People” (capitalist society), for it is a dying world on the edge of nothingness. Of course, the Invisible People are (with the exception of the real victims in this depiction, which according to Boorman are the Westerners) the whitest people in the film.

The Fierce People are the antithesis of the Invisible People – they raid and kill, they steal women, they cajole with drug dealers, and they speak, hunt, and dance while making guttural animalistic rumblings. And they, requiring a simple contrast to the light-skinned Invisible People, are black.

[It is interesting to note that the idea of the Fierce People originates from the studies of Napoleon Chagnon, who was in part responsible for The Axe Fight. Here we find another example of a seemingly “fictional” work pulling from the real. Yet here (and this argument could be made for Matthiessen’s information as well), Chagnon’s Fierce People are representations as made by Chagnon – essentially, the Fierce People as depicted in The Emerald Forest are coming to us through the eyes of an author through the eyes of another author, who may or may not be presenting the best interpretation in the first place. Were we to keep in mind the inherent difficulties in making a representation, we could view the representation in The Emerald Forest with some reservation. But the authority of both the camera frame, as well as the opening statement of legitimacy, further remove the viewer from the direct relationship between the author(s) of the representation(s) and the human representation(s) being made.]

Is this problematic situation, the creation of (damaging) authority, in part due to the representation being made on film? This idea is not very different from that proposed by Walter Benjamin: In order to view Boorman’s account as an accurate representation, does the single event of the loss of “the aura that envelops the actor…and with it the figure he portrays” (Benjamin, 229) not help further the account from the realm of fantasy? Is this not a condition of the moving picture, that an event depicted in this manner by its very nature looses its foundation in harmless fiction or Hollywood entertainment? After all, “The audience’s identification with the actor is really an identification with the camera,” (228) not the character the actor portrays. Once again, the authoritative voice of the camera frame steers us away from the obviously constructed aspects of the depiction and allows the director that much more control over the representation being made. (Though not in the scope of this paper, how well does this idea support the argument of media influence or violent entertainment influencing an audience through its own representations and authoritative framing?)

Furthermore, we can relate Benjamin to Clifford in the sense that the portrayer of an account – here, both director and the writer of ethnography – is aware of just what it is they are doing. Boorman knows what he is attempting with this particular representation, and for him our believing in the legitimacy of this account is paramount – if it was not, there would be no need for the film’s opening declaration.

For Clifford, the author, being unable to remove himself from the representation being made enters through this relationship into the realm of allegory with the work produced. Benjamin, in a similar vein, states that “While facing the camera [the actor, or director] knows that ultimately he will face the public, the consumers who constitute the market.” (231) Both the actor and the author are incapable of defining the relationships they have to their own respective products, though they know exactly what those relationships are. In a strange turn of events, the same frames which Boorman uses to legitimize his production become the frames by which his film will be dictated – the inclusion of fantastic events (the gun fights, the scenes of romance in the river) being the necessary precursor to mainstream Hollywood consumption while lending authority to the entire depiction.

When the film moves from the civilized cities and dust-covered dam construction yards to the dark, ominous forests and rivers of the Amazon, we jump from South America to the American South, circa 1950. Boorman has provided us with incredibly over-simplified depictions of two groups of people living in the Amazon, and has done so in a racist and simple manner. What is perhaps the most troubling of all of this is the illustration of the Cliffordian “redemptive Western allegory,” which occurs when the American Bill Markham seeks to undo the wrongs he has committed upon the environment by blowing up the dam his company built. Lucky for him (or rather, for us – the North American movie-going public), the surging river water and raging storm overhead are already too much for the man-made structure, and the dam collapses without his aid. In the end, Westerners really do want to make things better – thankfully, we don’t really have to.

Ultimately, I cannot help but feel the opposite for The Emerald Forest as I did for Matthiessen’s At Play in the Fields of the Lord. The question becomes, How can I accept (and even promote) one method of pseudo-fictional representation over another? Perhaps in the end the frames which Boorman utilizes to justify his interpretation are enough to tip the scales against him. Boorman states that his account is an accurate cultural representation, thus actively attempting to disallow the viewer the realization that his interpretation is just that – an interpretation. Maybe the only way to engage with Boorman’s representation of the diverse people of the Amazon is to know that it is truly a fiction, in the most basic sense of the word, no matter how much he may want us to think otherwise.

Part Four: The Holy Trinity of Representation

The Ax Fight by Timothy Asch and Napoleon Chagnon

Compare this sentence, presented at the beginning of Timothy Asch and Napoleon Chagnon’s film The Ax Fight, with that of Boorman’s from The Emerald Forest:

“You are about to see and hear the unedited record of this seemingly chaotic and confusing fight, just as the fieldworkers witnessed it on their second day in the village.”

Again, we are presented at the outset of a representation with the notion that what we are about to see is “real.” The Yanomamo we are about to watch, engaged in shouting, hitting and aggressively posturing toward one another, are really doing just that. There is nothing staged or “fictional” about the event. Furthermore, we are told that what we are seeing is “unedited,” basically that we need not concern ourselves with authorship (and all that issue entails), as what we watch is untouched, pure representation.

The method Asch and Chagnon use in their ethnography is a simple one. After the initial unedited presentation of a tribe-engulfing ax fight is made (the one which the introductory text refers to), we are provided with an abridged presentation of the same events with the author’s narration (seemingly for clarification), and then a third, edited version, of the same events.

Still from the film "The Ax Fight"

This three-part approach (unedited, narrated, and edited), provides the viewer with three seemingly distinct opportunities to view the information in this ethnography, each from its own stance of authority. It is in the first that we are led to believe that we are free from the allegorical underpinnings of the authors of the work. With the exception of the placement of the camera (on the fringes of the fight), there appears to be no other indicator that what Asch and Chagnon are showing us in this scene is anything other than documentation. There is no cutting of sequence, no editorial mixing – the depiction is one scene, taken from a distanced stance. Yet the key is in the fact that Asch and Chagnon are indeed showing us something. The documentary frame of the camera, which at once lends its authority to this representation, is still a frame as utilized by the authors. The point being that this seemingly unadulterated version of events is, despite the attempts at authority made with the initial statement, just as directed by Asch and Chagnon as was Boorman’s film.

This issue is furthered when we realize that this unfiltered representation does not hold enough from which we can gather any pertinent information. We are not privy to any of the context from which the complex interactions between the Yanomamo involved are drawn. It is only through the second representation (or, mimetic re-framing of the depiction) which Asch and Chagnon make – the narrated version, that what might be pertinent information is framed for our understanding. In fact, it is through the second representation that the first is legitimated, not – as it would appear – the other way around. For what I just termed “pertinent information” is really the information which the authors of this representation deem important (for example, a confrontation in the garden which leads up to the actual trading of blows and physical/verbal taunts or the history of bad blood between the two groups – all of which might or might not be important to a representation, though it is arguably important to the points the authors which to make).

Again the author enters, and with him all which his presence entails. We are once again situated in the problematic issue of a de-cultured, de-institutionalized, de-specified representation which is at the same time being presented to us as just that.

The question can be asked, Without the narrator’s information, how much would we know about the representation being made? It would seem that we would have no real context within which to read the data, we would be, in effect, lost among the borderless, (seemingly) frameless data. Yet with the narration, with the information provided by Asch and Chagnon, we are forced to engage the dilemma of representation. It is a double-edged sword, where questions give way to answers which in turn give way to more questions.

Now, when Asch and Chagnon present us with a third version of events (the edited version), a Matthiessen-like approach is utilized. Through this version, with cuts between scenes, breaks in the seamless visual flow, shifts from person to person and even repositioning of the newly created scenes, we see that there is an author present and that said author is capable of directing the flow of information as he sees fit. Regardless as to what the intent (or allegory) of the author is in this case, we can recognize the creation of an interpretation. And once again, the referential information (as already presented to us in earlier versions – see the construction of the representation taking place as we speak), coupled with the aesthetic concerns of cuts and sequencing, address the same creation of representation through a referentially-based fiction Barthes discusses. And like Matthiessen, the authors of this account have begun the process of their fiction feeding off of their realistic referents, which in turn strengthen their fiction – though here, the authority of The Ax Fight representation grows further: Now we can compare the representations made in the different versions, with each version supporting the next – essentially lending more credence and authority to the representation which Asch and Chagnon aim to make clear (the third, or edited), wherein their own aims and directions as ethnographers are presented to the audience: they have built up and legitimated their interpretation through yet another method.

Does this mean that Asch and Chagnon have found the best formula for ethnographic representation? It would seem that they have allowed themselves a magnitude of authority more than what exists in typical declarative statements and camera framing. They have built their representation in stages; each version of events is slightly more directed and framed than the last but draws on the authority of the previous version and concurrently creates a structured fiction. This is a system by which the interpretive representation of the authors is increased exponentially with each new version.

The strength that this multi-part ethnography has on its side is the same thing which makes this representation more problematic than most. After all, are there not alternative interpretations which Asch and Chagnon did not make? Throughout The Ax Fight we are presented with a representation which shows the men of the tribe to be the principle actors in the confrontation. Is this truly the case? Asch and Chagnon, in their second version of events (the narrated version) tell us that the Yanomamo altercation really began in the tribe’s garden, where a woman of one group grew upset with the idea of working for members of the other. Furthermore, throughout each of the versions we are presented with, the women of the tribe are seen yelling insults at the warring parties. Do the Yanomamo women have more influence in this ax fight than Asch and Chagnon lead us (or want us) to believe?

Whatever the answer, the point is that Asch and Chagnon set out to tell us something specific, and through their representation they seek to direct our attention to (what they hope will be) unambiguous situations which further their claims – here, that the Yanomamo men are the ones who raise and settle confrontations, and thus direct and control the tribe. That the authors set out from the onset to make us believe their interpretation of events to be absolute (the beginning statement, the various methods of framing scenes, etc.) illustrates that this representation is just as mired in the problematic nature of authorship and construction of interpretation as are all the others.

Though I would say that Asch and Chagnon have presented us with an incredibly complex (yet simultaneously simple) representation of the Yanomamo people and society, the nature of this representation makes it unfeasible for mass ethnography to utilize due to the multiplicity of its approach. Its success belies its limitability, its representation held hostage to its quantity. Yet it is the simultaneity of strength and weakness, complexity and ease which makes this account in the end so interesting to contemplate.

Conclusion

It would seem that in the end there does not exist such an animal as “perfect representation.” As I have illustrated, each attempt at representation is rife with its own successes as well as complications (and even failures). Indeed, it appears that the closest we can come to even a useful representation requires an examination of the other side entirely, coming closer to Stanley Fish in his incorporation of the audience into the representation itself – instead of directing our attention to the intention of the author, we need to look at ourselves, the audience, to see if we are capable of realizing the problematic nature of making representation, and from there move beyond this difficulty to find the useful information from which we can draw our own interpretations. If Clifford, Fish, White and Barthes are right (and I think they are), the most important job in the making of a representation falls to us, the viewers-reader-audience. It is at the point where we enter the account that the representation is actualized and given authority, and it is our own interpretation which will be infused in the reproductions we will make of the account, through the spoken- or written-word, or perhaps even other means (the film, the painting, the musical score – as they have been duly informed, finding vent and venue in their own more- or less-direct way). And here we become like Gregor with the Mehinaku – in one instant we become both audience and actor/author.

This idea can be furthered, as it would also appear that distinctions such as “fiction” and “non-fiction” are not as black and white as we might previously have thought. Indeed, invention and reality do more to serve the other than they do to define themselves. As we have seen with each of the authors of the investigated accounts, utilizing aspects of both fiction and non-fiction allowed for a reinforcing of the original referent (lending it authority by its very re-use) and subsequently refashioned a new referent, or a construction of reality to be used in turn. Matthiessen and Boorman did this more directly than did Gregor and Asch & Chagnon, yet even the Mehinaku and Yanomamo representations engaged in fiction at the very point those authors entered their work – when Gregor’s pencil touched his notepad, when Asch and Chagnon hit the record button on their camera. Again, “There are no moves that are not moves in the game.”

It would appear that “pure” anything is a misnomer, and that this exploration as presented here furthers the claim that binary systems rely on (at the least) two sides for the creation and validation of the other – even though those two sides (author/audience, fact/fiction) are often incontrovertibly wrapped up in and among each other. Fiction cannot exist without fact, and as the authors here attest, there is no need (or even possibility?) for the two to ever be separate. And what of the inverse, can fact exist without fiction? The real question is, Who’s telling you so?

References

Barthes, R.

1986 “The Discourse of History” and “The Reality Effect” from The Rustle of Language. New York: Hill and Wang

Benjamin, W. 1968 “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” from Illuminations. New York: Schocken Books

Clifford, J. 1986 “On Ethnographic Allegory” from Writing Culture. Berkeley: The University of California Press

1988 “Ethnographic Authority” and “Histories of the Tribal and the Modern” from The Predicament of Culture. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Fish, S. 1980 “What Makes an Interpretation Acceptable?” from Is There a Text in this Class? Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Gregor, T. 1977 Mehinaku: The Drama of Daily Life in a Brazilian Indian Village.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Matthiessen, P. 1965 At Play in the Fields of the Lord. New York: Random House

Rubenstein, S.

2002 Alejandro Tsakimp: A Shuar Healer in the Margins of History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press

Taussig, M. 1993 Mimesis and Alterity. New York: Routledge

White, H. 1980 “The Value of Narrativity in the Representation of the Real” from

On Narrative. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press